Following my February 2007 Massage Today column on sacroiliac joint syndrome, I received several e-mails from therapists asking how to differentiate low back, sacroiliac and piriformis syndrome pain. The first distinction needing clarification is that piriformis syndrome is considered a “functional entrapment syndrome.” The word “functional” describes neurological compression disorders resulting from positional or kinesiological factors that are not solely linked to structural or inflammatory conditions. Therefore, clients presenting with piriformis syndrome typically only experience sciatic-like symptoms during certain movements or when pressure is applied to the affected area (Fig. 1– reprinted with permission of Medical Multimedia Group).

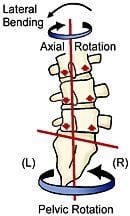

Sacroiliac and piriformis syndrome anatomy is comprised of many complicated elements involving bone, muscle, connective tissue and nerves. Understanding this anatomy helps reveal the difficulty that exists when developing a healing program for these often-debilitating conditions. Frequently, piriformis syndrome pain begins as the external femoral rotator balance that is distorted by pelvic obliquity, due to conditions such as backward sacral torsions, iliosacral inflares and foot hyperpronation. The most common and tormenting of the sciatic-like SI dysfunctions is called a right-on-left backward sacral torsion. It occurs when the sacrum gets stuck rotated right and side-bent left between the two innominates (Fig. 2).

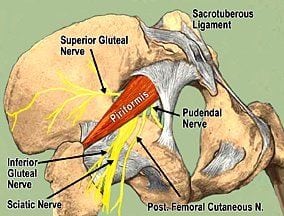

Typically, backward torsions involve a lifting incident, during which the person bends forward and side-bends left at the lumbosacral junction. Intervertebral discs, facet joints, sacroiliac ligaments and piriformis muscles are most vulnerable to injury in this position. However, the movement that precipitates the greatest long-term discomfort takes place when the person attempts to straighten up while L5 is side-bent left and rotated right. As L5 jams backward into the sacrum, sharp, burning sciatic pain shoots into the buttocks and down the leg. Unfortunately, backward torsions commonly are mistaken for disc pathology, causing many unneeded and unsuccessful surgical procedures. Prolonged ligament and joint capsule stress caused by an unstable (crooked) sacroiliac joint can sympathetically spasm the piriformis muscle, causing contracture, fibrosis and sciatic impingement (Fig. 3), even though a torsional SI joint fixation may have been the culprit responsible for initiating the sciatic assault. Soon, the fibrotic piriformis escalates the symptoms by trapping the nerve between it and other muscles, ligaments or bone in the sciatic notch. The end result of this double-crush disorder is neural breakdown and interruption of the axoplasmatic flow of vital nutrients. Some researchers estimate that double-crush syndromes occur in as much as 40 percent of the sciatic population.1

Hamstrings and Piriformis Role in SI Dysfunction

Double-crush sciatic pain often originates from a piriformis injury brought on by lifting or overuse. As the L5 facet joints glide forward on the sacrum during trunk flexion, the piriformis and sacrotuberous ligaments must restrain the sacrum from moving forward (counternutation). Regrettably, tendon and ligament fibers are vulnerable to microtraumatic tearing during this bending/twisting maneuver. Because the piriformis partially originates from the sacrospinous ligament, which is fascially linked to the hamstrings, trauma or overuse can create adhesive scar tissue that shortens the piriformis and drags on the sacrum. Prolonged unilateral sacral drag leads to ligament hypermobility, inflammation and sacroiliac imbalance. When the hamstrings and piriformis destabilize the SI joint, other nerves (superior and inferior gluteal) become inflamed, causing symptoms resembling piriformis syndrome (Fig. 4).

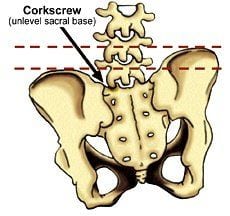

Since the nerve supply for the glutei, tensor fascia lata and piriformis muscles does not travel under or through the piriformis with the sciatic nerve, any signs of denervation (muscle weakness or atrophy) may indicate SI dysfunction, which might be co-present with piriformis syndrome. Often, only one piriformis will be SHORT and tight, forcing the sacrum to shift laterally on its long axis. This sets the stage for yet another painful compensatory problem at the lumbosacral junction, known as an apex shift. According to Retzlaff, et al.,2 apex shifts cause the sacral base to rotate anteriorly, resulting in a deep sacral sulcus on the side of the tight/short piriformis. This unleveling of the sacral base creates a lumbar spine rotoscoliosis (corkscrew), which can compensate and twist all the way up to the O-A joint (Fig. 5).

Low Back Joint Pain Treatment Options

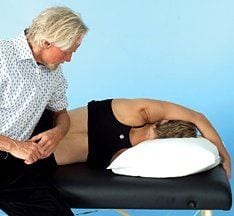

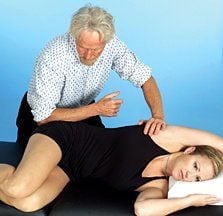

Since pelvic imbalances are a major contributing factor in all low back and piriformis dysfunctions, it makes sense for the manual therapist to first develop a therapeutic strategy for establishing iliosacral and sacroiliac alignment. Fig. 6 demonstrates an effective elbow technique for correcting an upslipped left innominate. This iliosacral condition frequently is seen in people who bear weight on the left leg during prolonged standing. As the client gently pulls up on the therapy table while performing slow pelvic tilts, the therapist’s elbow slowly releases fibrotic erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, latissimus dorsi and iliolumbar ligaments, allowing the innominate to drop inferiorly. The IMPORTANCE of the iliolumbar ligaments cannot be overlooked. Their primary function is preventing excessive lumbar side-bending, but they can become major sciatic pain generators when fibrotic. Because the iliolumbar ligaments form fascial hoods over the sciatic nerve when strained, they rub on the nerve’s dural sheath, contributing to double (or triple) crush syndromes.

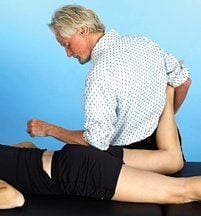

In summary, piriformis syndrome should not be treated as an isolated event, even if tests such as the Pace, Freiberg and Beatty are positive. A stable pelvis, derived through proper upper and lower quadrant balance, is essential for long-term correction of sciatic nerve conditions. All ligaments and muscles attaching to the pelvis from above and below should be tested and balanced. Once the low back and pelvis are functioning properly, piriformis techniques that address the muscle’s origin and insertion, such as those shown in Fig. 7 and Fig. 8, usually are effective in relieving pressure on the sciatic nerve … but not always.

Medical Breakthrough

Although sciatica is the most common condition treated by neurosurgeons, piriformis syndrome rarely is mentioned in the majority of neurology textbooks, with only a minimal number of U.S. surgeons trained to properly treat the condition. For the past 75 years, sciatica has been thought to be caused by a herniated disc and treated accordingly. Now, researchers at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center; the University of California, Los Angeles; and the Institute for Nerve Medicine in Los Angeles have developed a new nerve-imaging technology called magnetic resonance neurography. The technology has proven extremely effective in implicating piriformis syndrome as a causative factor for sciatic leg pain in the majority of patients who had failed diagnosis with traditional MRI scans and/or were not treated successfully with surgery. The researchers evaluated 239 patients whose symptoms had not improved after diagnosis or treatment for a herniated or damaged disc. All patients received a detailed neurological exam and had a thorough review of all previous scans and treatment history to rule out any condition that might have been missed.

Results of the study confirmed that 69 percent had piriformis syndrome, while the remaining 31 percent had a combination of other nerve, SI joint or muscle conditions. Researchers using these active diagnostic techniques found piriformis syndrome to be a more common cause of sciatica than the herniated disc.3 To treat piriformis syndrome, Dr. Filler, et al., injected a long-acting anesthetic into the spine, muscle or nerves. About 85 percent of the patients obtained some relief from the injections, which helped relax the piriformis muscle spasm. However, relief was not long-lasting and 62 patients required surgery to correct the syndrome. Of those, 82 percent had a good or excellent result during the six-year follow-up.

This groundbreaking study, published in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine, will surely help medical and manual therapists weed out complex diagnostic conditions such as sciatica – a condition that affects nearly 40 percent of adults at some point during their lifetime. Therefore, it behooves today’s touch therapist to recognize the clinical signs of piriformis entrapment and all associated double-crush syndromes. Fortunately, now that reliable imaging tests and surgical treatments are available in most major hospitals, we must embrace one of our foremost fundamental therapeutic adages: If in doubt, refer them out!

On sale this week only!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course!

NEW! Enhanced video USB format!!!

Learn unique approaches to work with the shoulder girdle, arms, neck, and torso, this course will prepare you to relieve painful myoskeletal issues in the upper body. Through video demos and animation, you’ll learn to identify several compensatory movement patterns and their associated reflexogenic pain. With this understanding of where the true source of problems arise, you’ll be able to develop highly effective treatment protocols and deliver lasting results. This course provides you with the skills you need to confidently relieve pain issues in the upper body. (20 CE)

Bonus: When you order the Home Study version, get the eLearning course and and an additional 2CE Ethics eCourse for free!

Save 25% off the Upper Body Course this week only. Offer expires Sunday, March 1st. Click the button below for more information and to purchase the course for CE hours and a certificate of completion to display in your office.